By Cerren Richards, PhD. Candidate, Ocean Sciences, Memorial University.

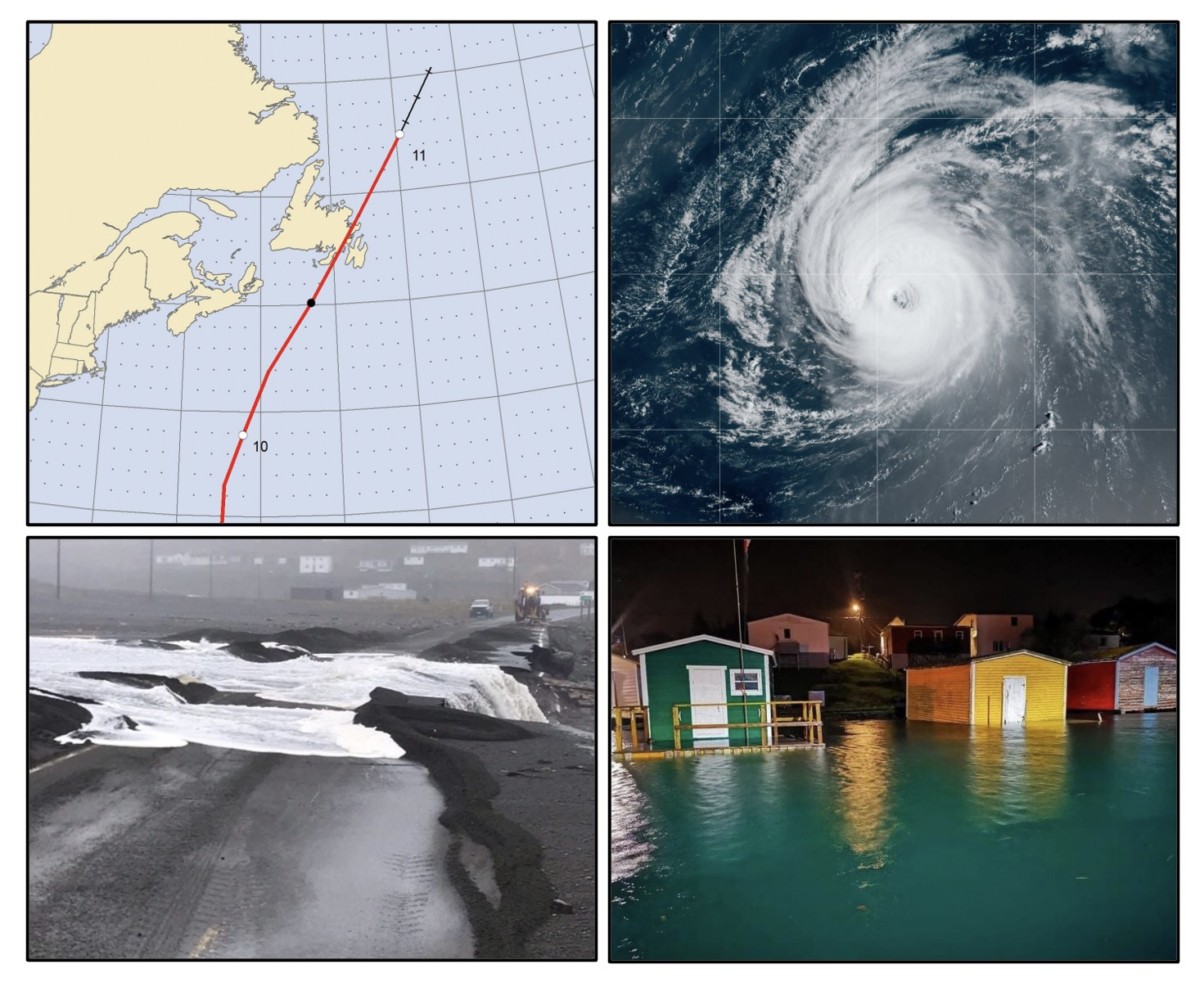

Hurricane Larry battered Newfoundland in September 2021 with intense wind gusts over 180 km/h, torrential rains, and a powerful storm surge. While we all took shelter inside our homes, Larry’s fury caused extensive damage to buildings and roads, and left thousands without power for days. This was an ‘extreme climate event’, a short-term, but chaotic weather condition that was more severe than typical Newfoundland weather. Extreme weather events, such as storms, cold spells, and flooding, are predicted to substantially increase in frequency and intensity throughout the North Atlantic. These events pose many challenges for species and could be particularly problematic for seabirds. Climate change and severe weather are already top threats to seabirds, impacting more than 170 million individuals worldwide. Newfoundland and Labrador is the seabird capital of North America and home to a globally significant number of nesting and wintering seabirds. Therefore, the province and adjacent waters are important areas to study because millions of seabirds may potentially be impacted by extreme weather events now and in the future.

My PhD research is investigating the impact of extreme weather events on Atlantic puffins and Leach’s storm-petrels on Gull Island in Witless Bay Ecological Reserve, Newfoundland. Both species are threatened and classified by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as ‘Vulnerable’ with decreasing population trends. Therefore, vital research and conservation is needed to halt their declines and promote their recovery.

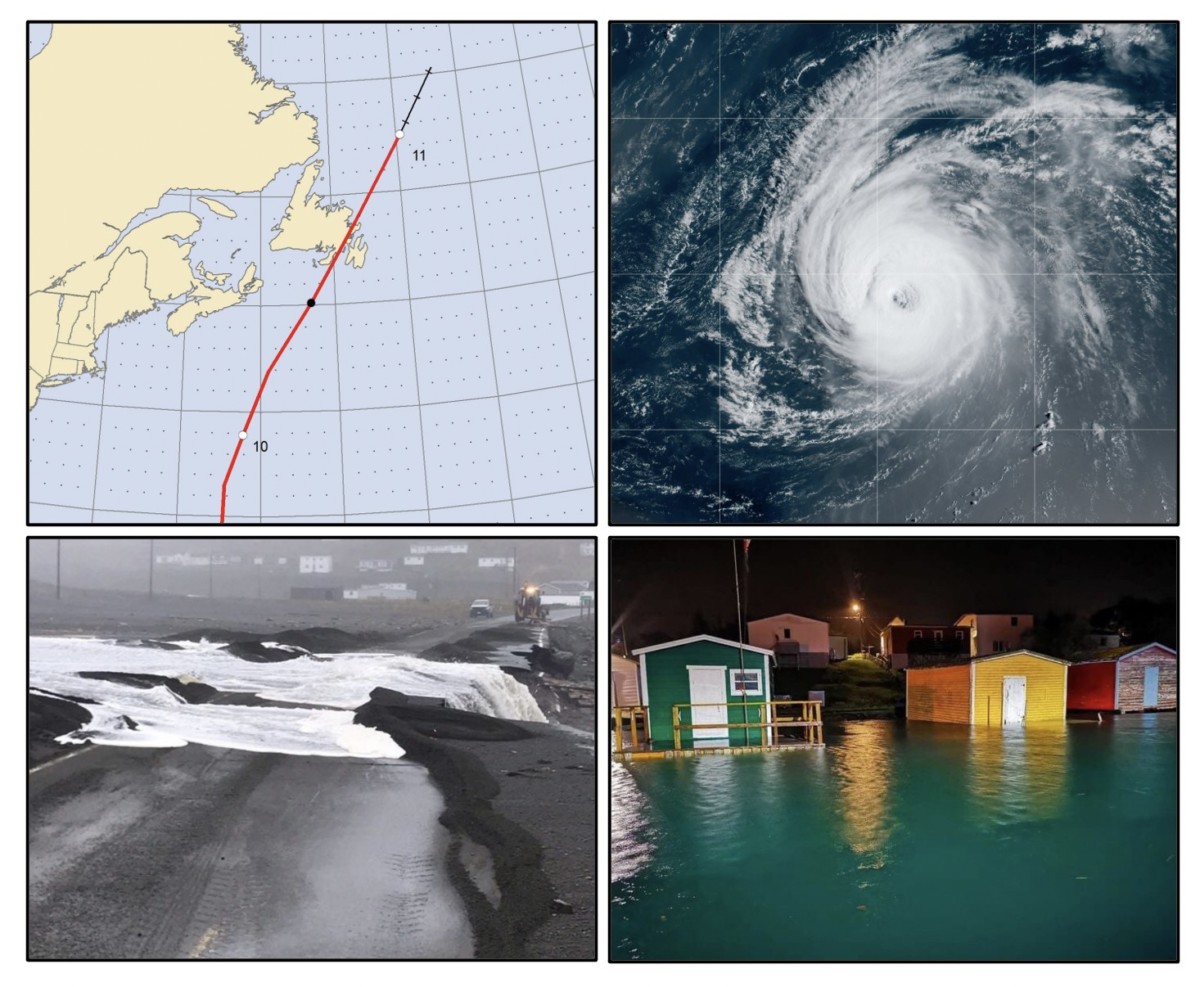

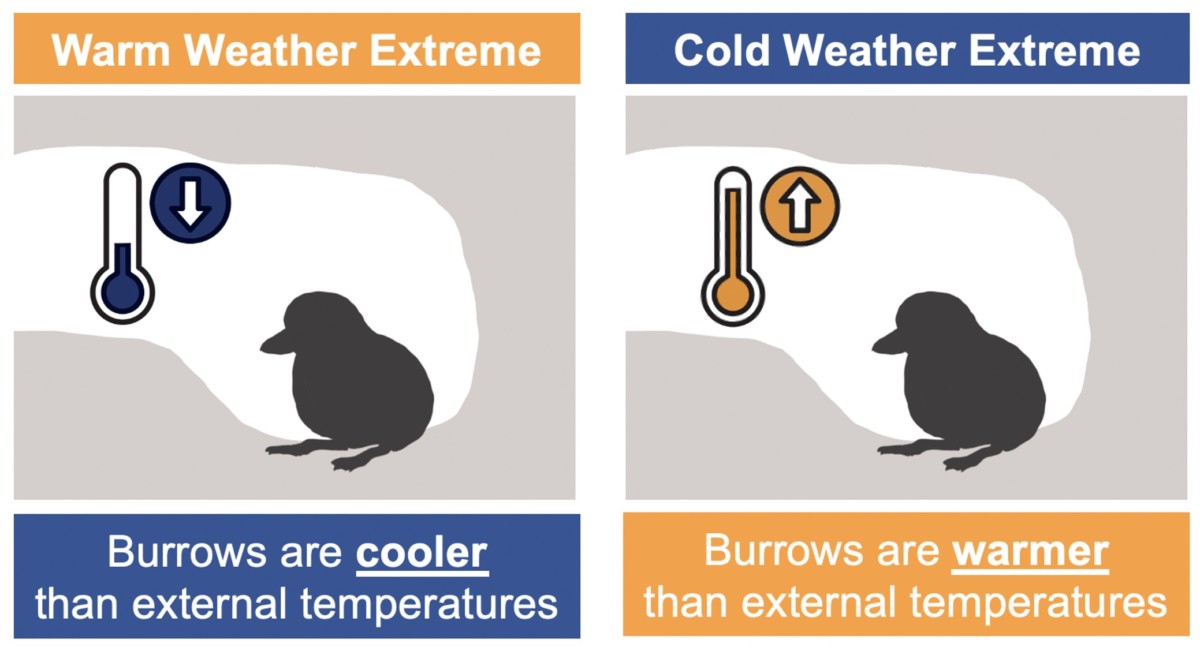

Extreme weather has the potential to negatively impact both species. The Atlantic puffin breeding season is concentrated during peak summer heat, while hurricanes and cyclones occur during the mid-late breeding season for Leach’s storm-petrels. Chicks may be particularly vulnerable to extreme events because they are predominantly left alone from 6 days old, at which time they are only the size of a golf ball (Leach’s storm-petrels) and tennis ball (Atlantic puffins). Chicks experiencing prolonged heat may suffer from heat stroke, while cold weather could lead to hypothermia. To protect their chicks, one method that both species have adopted is their unusual choice of nesting location. Interestingly, both the Atlantic puffin and Leach’s storm-petrel nest in burrows, similar to rabbits. The sheer abundance of these burrowing seabirds visiting Gull Island during the breeding season has resulted in thousands of burrows scattered across the island. As a result, the island’s surface now resembles a gigantic chunk of Swiss cheese. Burrow nests can have multiple benefits over open nests. While open nests are exposed to the elements and chicks can experience high death rates if extreme events hits, burrows shield chicks from the weather and may even minimize the impacts, just like our homes during a storm. Yet, it is currently not known how much thermal protection burrows provide chicks during adverse weather conditions.

To tackle this unknown, we placed miniature temperature loggers in the burrows of Atlantic puffins and Leach’s storm-petrels to record the burrow’s internal temperatures through the 2021 breeding season. We tested whether the chicks within burrow nests are protected from the harsh outside temperatures. A number of heat events and intense storms hit the island whilst the seabirds were still breeding, including Hurricane Larry and Sub-Tropical Cyclone Odette. Our temperature loggers captured these events and provided insights into seabird burrow environments.

We found that burrows are keeping nests around 7-8°C warmer during extreme cold weather for both species. Whereas in extreme warm weather, Leach’s storm-petrel burrows were 9°C cooler than outside temperatures, and Atlantic puffin burrows were 5°C cooler. The bottom line is, these burrows can provide a direct line of defence for seabird chicks against current and future extreme cold and warming events. They act as buffers against sudden temperature changes and likely protect the chicks from hypothermia and overheating.

The difference in temperature between the two species’ burrows during warm extremes is likely because Atlantic puffin burrows are located on grassy slopes, in close proximity to the ocean, and fully exposed to the summer sun. By contrast, Leach’s storm-petrel burrows have an additional layer of protection from foliage, such as ferns and trees. Since Atlantic puffin burrows are less effective at keeping nests cool during hot weather, the chicks may face problems in the future given warming temperatures driven by climate change. Atlantic puffin burrows may therefore need conservation measures to reduce nest temperatures during extreme events. Borrowing and adapting conservation methods from other endangered species, such as sea turtles, could hold the key. For example, conservationists use ‘nest shading’ to reduce turtle nest temperatures by building small shade structures over egg clutches. This could be a promising avenue for protecting seabird chicks from future extreme events and merits future investigation.

Dr. Leslie M. Tuck’s pioneering work inspired the province of Newfoundland and Labrador with the wonders of natural history and raised awareness of avian conservation. Unfortunately, with increasing climate change threats, seabirds need our attention now more than ever. We must continue to expand upon Tuck’s conservation efforts to preserve seabirds in Newfoundland and Labrador. I hope my PhD research can be used to identify the species that will be most vulnerable to environmental change in the future to guide targeted conservation actions for our iconic seabird species.

Connect with Cerren Richards:

Website: https://www.cerrenrichards.com/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/CerrenRichards